In the Middle Ages, responsibility for the poor was in the hands of religious orders, usually to be found in the monasteries. In the middle of the 16th century, after the dissolution of the monasteries, the problem of looking after the poor became critical.

The increase in population was another factor and the poor people were often seen wandering around the country.

For many, the solution was to send the poor to fill up the new colonies in Virginia and beyond. In 1572, it was a criminal offence to be a vagabond and compulsory poor rates were introduced in the parishes.

The Poor Law of 1601 mentioned the “lame, impotent, old, blind, and other among them being poor and not able to work” and required the administration of poor relief in the parishes where the inhabitants had to take care of their “own poor”.

These laws were a mixture of charity and harshness, especially in the punishment of able-bodied people.

The 1601 Law

The 1601 Law was still in force right into the 19th century. In the first half of the 18th century, this paternalist system seemed to many to work reasonably well, especially as the population only increased very slowly and food prices were not too exorbitant for the poor.

In the latter part of the century, however, with the onset of the Industrial Revolution (1760-1830), the Law started to break down, with rising food costs, rapid population growth and a relative decline of rural society, and rapid growth in the new urban centres.

Before the Industrial Revolution, the master-peasant relationship was harsh but was complex, and relied on human contact. The peasant was surrounded by his family, living in a (rural) community, often for generations.

The employer-worker relationship of capitalism created a new relationship between classes, based on the cash nexus, and relentless production rhythms, with little place for leisure.

Gilbert’s Act

In 1782, Gilbert’s Act modified the Poor Law: it was passed to counter the increasing cost of the system and enabled parishes to work together to form larger Poor Law Authorities. They could, for instance, pool efforts and share a common poorhouse.

In 1795, as a consequence of the economic turmoil in the wake of the French Revolution and of the wars between European nations, magistrates in the Speenhamland decided to subsidize the wages of agricultural workers according to the number of children they had. This was known as the Speenhamland system.

There were many critics of the Poor Laws, though not all criticized the same aspects. Some seemed to criticize the undeserving poor (Malthus, Ricardo) while others advocated a more compassionate and universal system (Owen, Paine).

The end of the Napoleonic Wars and the poor harvests of the 1820s led to many country ratepayer landowners, who had to pay for a large percentage of the Poor Law benefits, complaining about the rising costs of such poor relief, which rose from £5.7m in 1823 to £7m in 1831 (see Murray, Poverty and Welfare 1830-1914, 1999).

Also, there were allegations concerning corruption in the administering of the local Poor Laws. Finally, it was claimed that the Speenhamland system actually encouraged women to have more children to have higher benefits. The 1821 Census seemed to confirm the rise in population.

The Poor Law Amendment Act (1834)

The Poor Law Amendment Act (1834), inspired by utilitarian and Malthusian principles (its architects were Edwin Chadwick and Nassau William Senior, both disciples of Jeremy Bentham, the founder of utilitarianism), was based on notions of discipline and frugality.

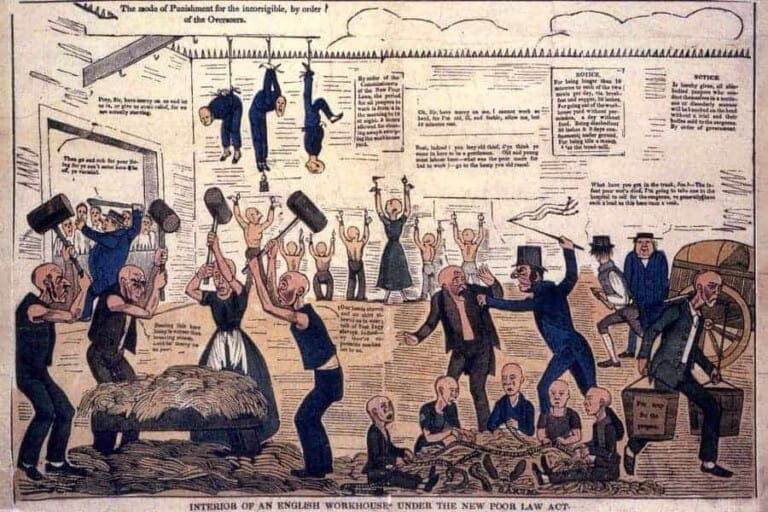

In addition, the (Whig) Government aimed to reduce public expenditure and make the poor more “responsible” for their own well-being: this involved the ending of “outdoor relief” and the setting-up of “workhouses”, often compared to “Bastilles”.

The aim was to dissuade all but the very hopeless from seeking assistance since poverty was the fault of the individual and should not only be discouraged but even punished.

Poor Relief was set at a level below the level of earnings of a labourer “of the lowest class”. The Poor Law Amendment Act was passed in the context of deciding who among the poor was deserving and who was not.

This important link between poverty and morality characterizes the 19th century. It was felt by some that helping all poor people would encourage and indeed reward immorality.

The workhouse was seen as a chance for the deserving poor to show their willingness to work hard in exchange for help at a difficult time in their lives. In so doing, they could regain their self-esteem and their position in society. However, the draconian conditions in the workhouse would dissuade the shirkers from seeking help.

The first reports on poverty and the living conditions of the poor were carried out in the 1830s. Kay, a Manchester doctor, set up the Manchester Statistical Society to look closely into the amount of poverty in the industrial North West.

Gaskell was more interested in the manufacturing process and the concentration of production capacity to reduce costs.

Chadwick, as one of those who proposed the introduction of the workhouse, supported his analysis with a formal stance. It was his report which would lead to the introduction of the 1834 Act.

Thompson believes the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act was “perhaps the most sustained attempt to impose an ideological dogma, in defiance of the evidence of human need, in English history”. According to him, the Act was impossible to apply fully, unduly harsh, doctrinaire and the wrong answer to a serious social problem.

Historians do of course differ as to an interpretation of the consequences of the Act. It seems to be fair to say that the act was of great significance and was hated by the poor.

The issue of poverty and assistance cannot be simply reduced to the class struggle: poverty and assistance are situated on different levels, sometimes between classes but also sometimes within the same class.

According to Poirier (“Pauvreté et assistance: Dramatis Personae” in Revue de Civilisation Britannique, Vol.6 n°2, Jan. 1991), the terminology has changed over the years: in the Middle Ages, the poor were assimilated to beggars.

Later, the poor were assimilated to peasants and later still, to peasants who had lost their land after the application of the enclosure laws.

In the 19th century, the poor became assimilated into the industrial labouring classes. This is not surprising considering that in 1830 the majority of the British population lived in the countryside whereas, in the 1851 Census, it was revealed that slightly more than half the population in England and Wales were living in towns or cities.

The factors affecting the rural poor and the urban poor have to be carefully appreciated. For the former, for instance, the weather could have a significant effect on harvests and so contribute to poverty.

For the latter, for example, trade cycles or foreign wars (the American Civil War…) could affect employment, and wages and thus contribute to poverty.

Reminder

Thomas Malthus (1766-1834) believed that since the population increased more rapidly than food production, everything should be done to control population increase.

According to him, the 1601 Poor Laws reduced the will to save and to make provision for the future among the common people.

David Ricardo (1772-1823), influenced by Adam Smith and Thomas Malthus, believed in the free market with few governmental controls: any attempts to “subsidize” incomes would have a distorting effect on the economy. He was hence against the Speenhamland system.

Synopsis » Inequalities in Great Britain in the 19th and 20th centuries

- Ante Bellum, Inter Bella : Legislation and the Depression

- Electoral inequalities in Victorian England: the Road to Male Suffrage

- Inequalities in Britain today

- Inequality and Gender

- Inequality and Race

- More electoral inequalities : the Road to Female Suffrage

- The Affluent Society : poverty rediscovered?

- The Beveridge Report: a Revolution?

- The Poor Law Amendment Act (1834)

- The Thatcher Years : the individual and society

- The Welfare State: an end to poverty and inequality ?

- Victorian philanthropy in 19th century England